Mother Tongue

“Unlike

a camera, which creates an image by focusing light through an aperture,

scanners operate by shining light onto the object and using mirrors to direct

its reflection onto a photosensitive surface. If the photographic image is a

trace, the scanned image is a kind of endless deferral – an abstraction with

the misleading presence of a double. Like the corridor of mirrors through which

the visitor must enter the exhibition space, each image in Mother

Tongue is a play of reflections that never leads back to the

real object.”

Abstract from curatorial text by Eugenie Shinkle

January 2022

Full text below.

Abstract from curatorial text by Eugenie Shinkle

January 2022

Full text below.

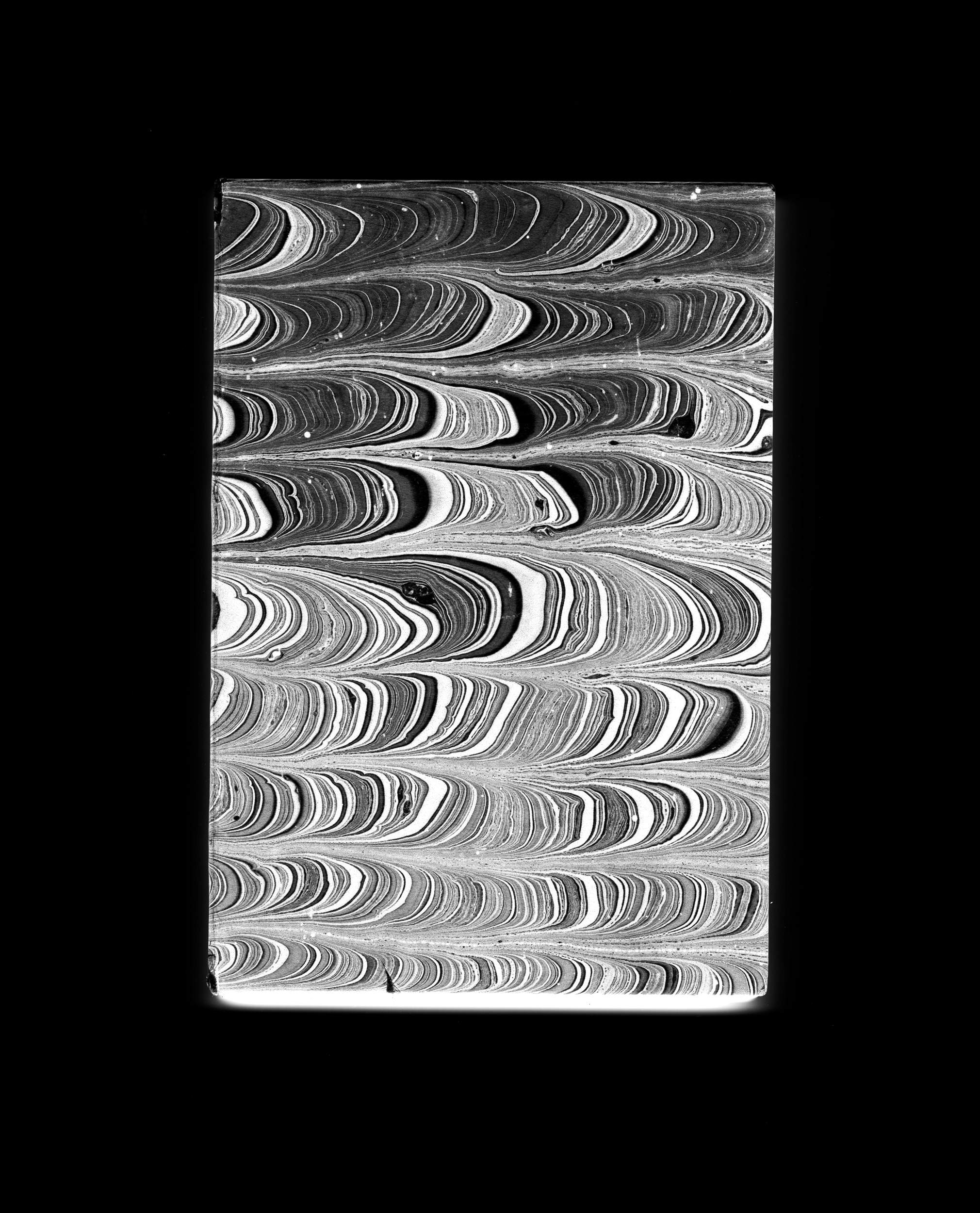

Critical Frequency

50 x 40”

Giclee print on aluminium

Artists frame

Mother Tongue

Channel separated audio, 30 min. looped

Audiocassette tape, cassette deck, amp, mirrored housing, speakers

2022

Installation views

Galerie NoD, Prague, January 2022

‘Want kommt der Morgen.’ The sentiment in this short phrase can’t readily be translated into English. In the original German, it carries a weight of melancholy that is lost when it’s transposed into another language. Peter Watkins’ mother left behind many such reflections, written on scraps of paper or carefully set down in notebooks.

Watkins’ mother died when he was a child. For more than a decade, he has been using photography to explore the themes of memory, trauma and familial loss, taking as his subject the few possessions that his mother left behind. In an earlier body of work, The Unforgetting, he created still-life images from some of these objects. The resulting photographs bear the unmistakable stamp and style of their maker – the past, viewed through the lens of the photographer’s present. With Mother Tongue, Watkins steps back from the camera and allows his mother’s voice to be heard alongside his own.

There are no photographs in this exhibition. The images of his mother’s notebooks, of the shorthand notes and poems that she wrote to herself, and of the audiocassettes on which she recorded herself practicing English grammar – all of these were made on a scanner. They are presented here as negatives, although that reversal is not always obvious. What is notable are the themes of untranslatability that unite them – coded messages, abstractions, and exteriors that reveal nothing of their contents. Though they resemble their subjects, they are not documents, but metaphors for absence and loss.

Unlike a camera, which creates an image by focusing light through an aperture, scanners operate by shining light onto the object and using mirrors to direct its reflection onto a photosensitive surface. If the photographic image is a trace, the scanned image is a kind of endless deferral – an abstraction with the misleading presence of a double. Like the corridor of mirrors through which the visitor must enter the exhibition space, each image in Mother Tongue is a play of reflections that never leads back to the real object.

In the final room of the exhibition, two mirrored sound columns face each other. From one, we hear a recording of Watkins’ mother, carefully translating from her native German into English; from the other, Watkins translates from his native English back into German. What sounds like a dialogue is two separate recitations, sharing the same physical space, but recorded decades apart. The voice, like handwriting, is an embodiment of language and the trace of a body. Here, it evokes both presence and irrecoverable distance. A parallel contradiction is enacted in the deliberately distorted scans that turn their subjects into abstract patterns, while faithfully recording, in digital form, the creases, tears and scuffs on the original objects.

‘Why do we live’? Watkins’ mother asks in one of her notes to herself. There’s no simple answer to questions like these. Mother Tongue looks back at a past that is similarly unknowable, not in the expectation of finding answers, but in order to explore the flaws and fissures in the process of remembering. It confronts the limitations of language and the inaccessibility of someone else’s anguish with our own longing to find meaning in what has been left behind. And in doing so it shows us not the false comfort of closure, but the value of learning how to live with loss.

Curatorial text by Eugenie Shinkle based on conversations with the artist

January 2022